1960s

1960

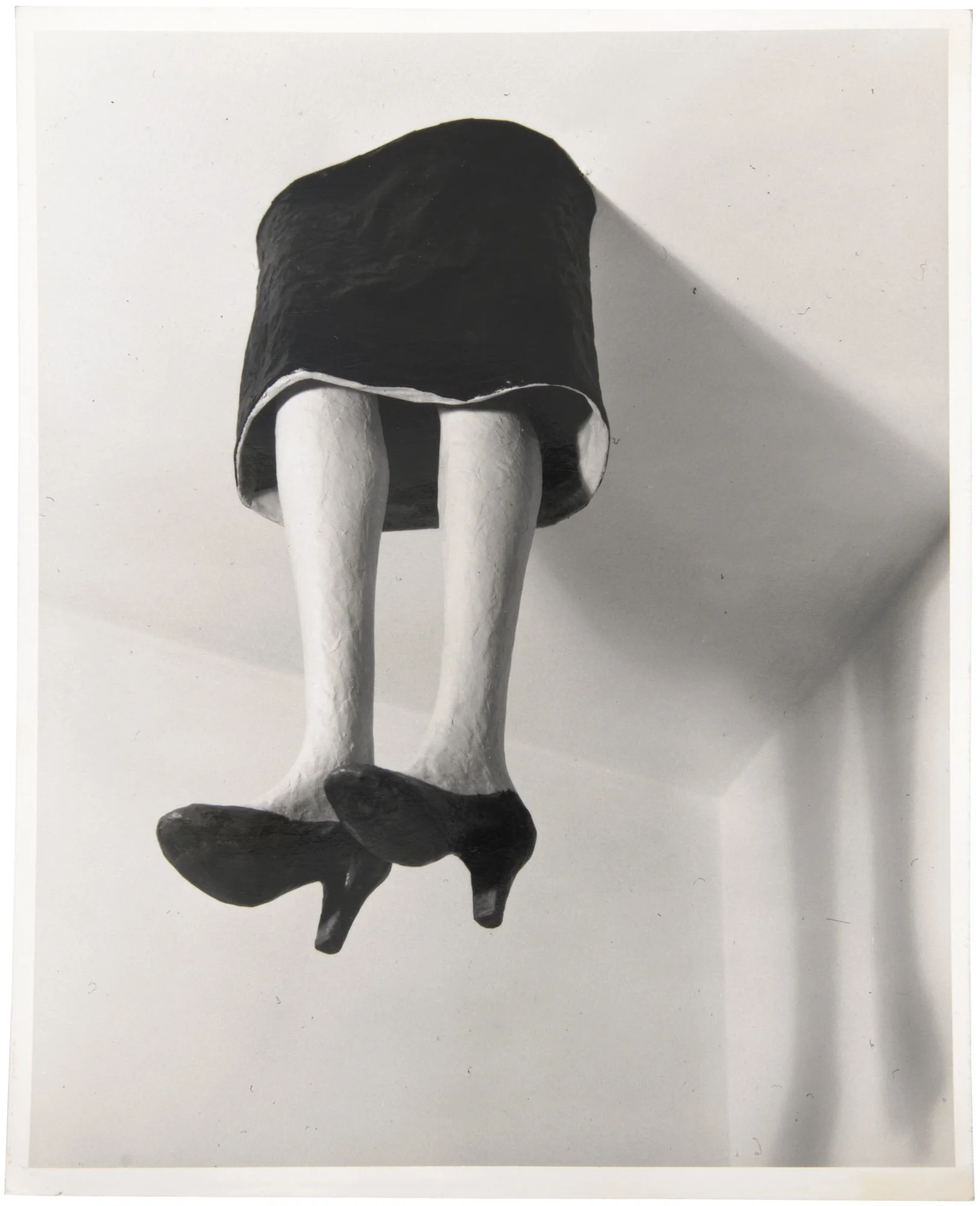

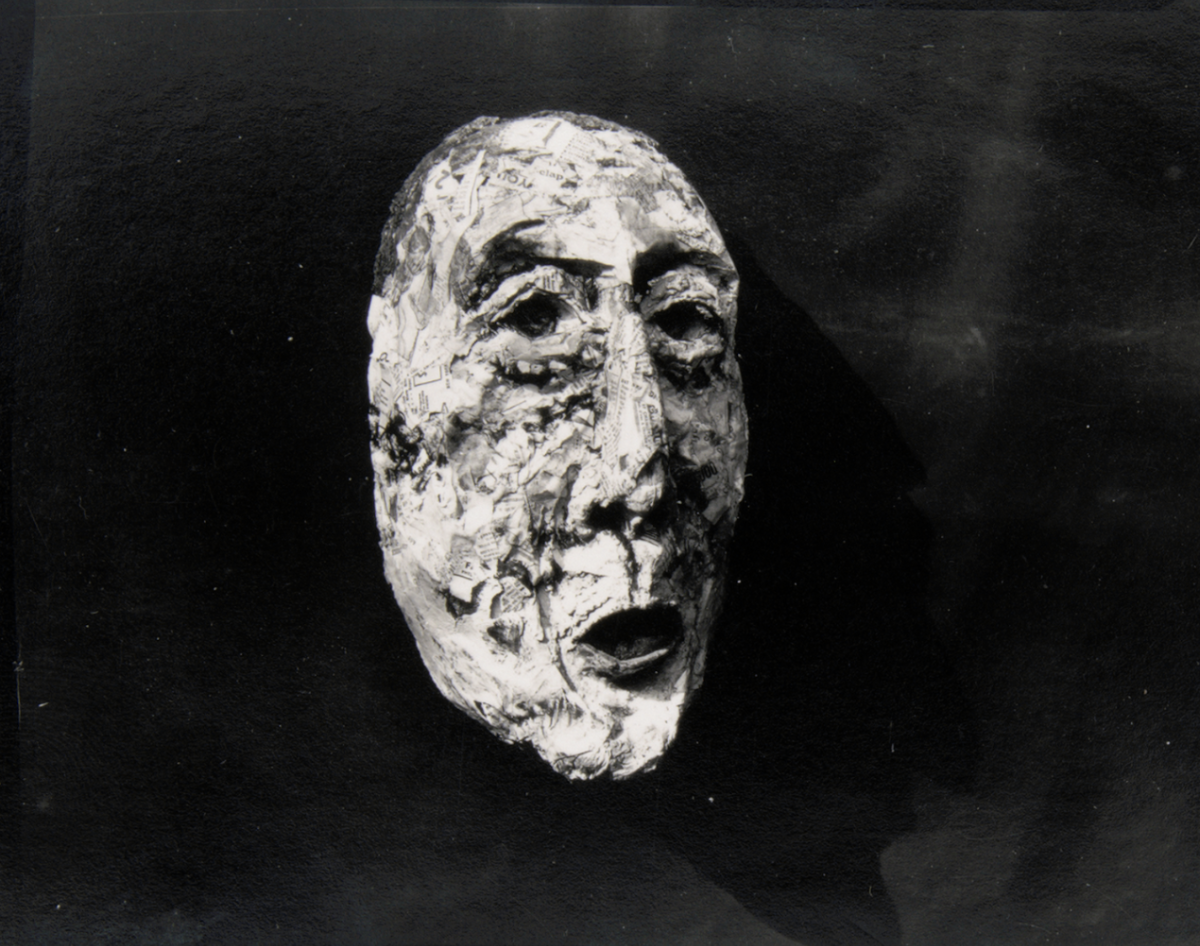

Receives his second solo exhibition at Poindexter Gallery, on view from September 20 to October 8, 1960. The show includes drawings and sculpture, including the first instances of female figures that anticipate the cloth and fabric sculptures he will begin in 1964; his first bronze, the seven-foot-tall Standing Man (1960); and a floor work in concrete, Sleeping Figures (1959). Ellie Poindexter hangs the painted papier-mâché Mary Jane as I Knew Her (1958) over her desk. The artist, teacher, and critic Lawrence Campbell who reviewed contemporary painting and sculpture in New York for nearly four decades, enthuses in ARTnews: “Paul Harris, in this sculpture and drawing show, creates a special ambiance of surprise, of theater . . . suddenly things seem possible. Instead of making a sculpture and calling it a woman, Harris finds a woman (in this instance, a mannequin) and calls her a sculpture . . . Somewhere else, two female legs poke through the ceiling, and in the center of the room there is a ‘real’ door with Eve in paper glued to the other side. All these pieces have an essentially magic quality—both for Harris and for the spectator. The figures seem to be alive.”²⁴

Eve, c. 1950s, medium and dimensions unknown

Mary Jane as I Knew Her, 1958, painted papier-mâché, 29 x 14 x 12 in.

The New York Times art reporter and critic Stuart Preston, enthuses: “Finding a category for Paul Harris’s astonishing work at the Poindexter Gallery is no easy matter. A first impression of the white plaster figures whether whole, truncated, or chopped up into separate pieces, is that of wandering into Madame Tussaud’s on moving day . . . Then are the big creased plaster shapes that resemble weapons for a pillow fight, or taffy blown up grotesquely. Harris has no end of manual skill at his fingertips, which the excesses of his fantastic, surreal ideas do not disguise.”²⁵

Receives Longview Foundation Grant and prepares to move, with his family, to Chile.

“Harris has no end of manual skill at his fingertips, which the excesses of his fantastic, surreal ideas do not disguise.”

Stuart Preston, The New York Times

Installation view of Paul Harris at Poindexter Gallery, New York, 1960

Plaster Landscape, 1959, plaster, 48 x 24 x 3 inches

1961

Appointed Fulbright Professor and Artist in Residence at Universidad Catolica in Santiago, Chile.

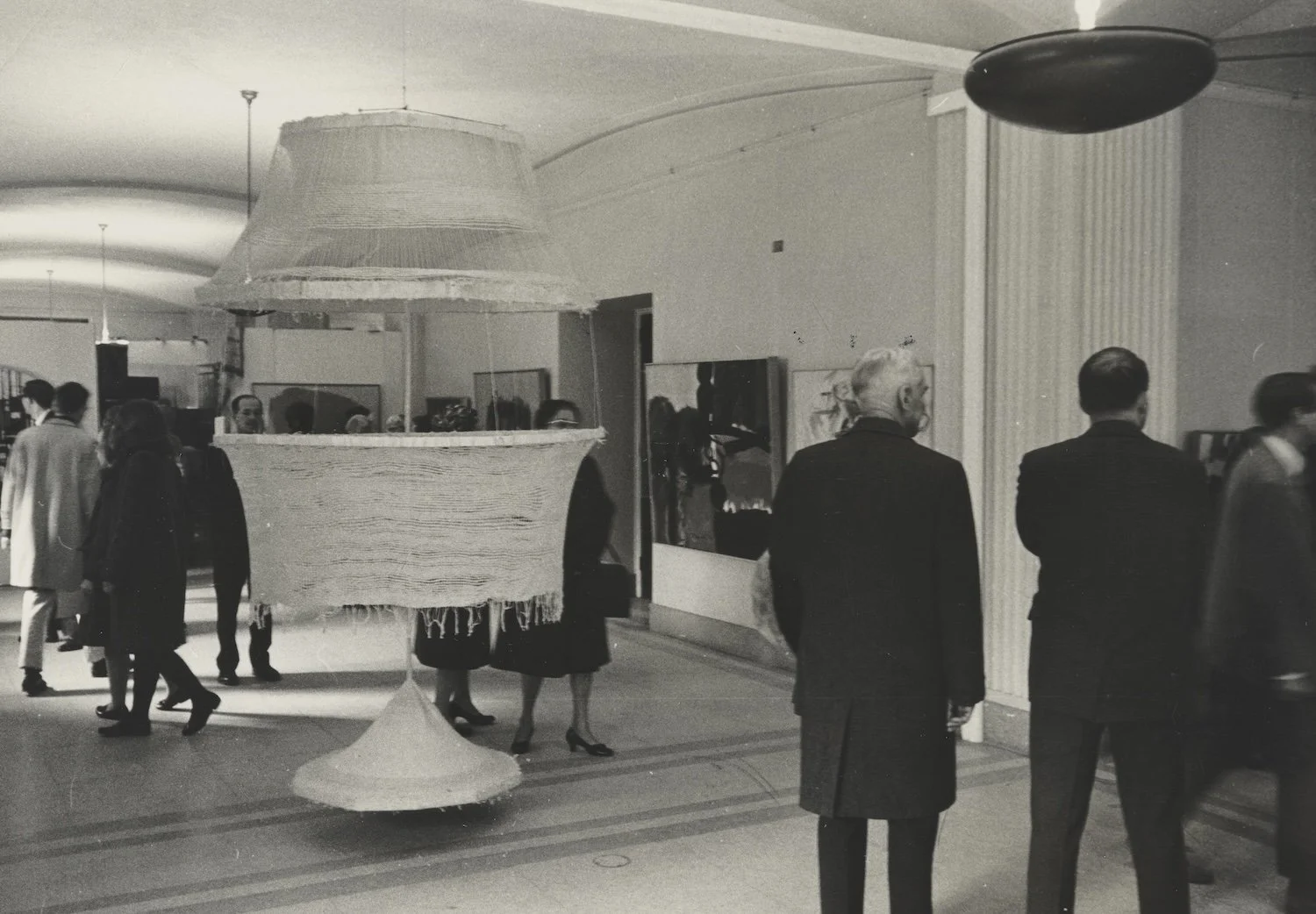

Harris continues to work in string, an available, inexpensive, and portable material that the artist, in a 1964 interview, will say “ship[s] cheaply without breaking.”²⁶ Artist and art professor Morris Yarowsky (1933–2006) will later remark in Paul Harris Drawings (1988), “As a Fulbight Fellow in Chile during 1961 and 1962 he made a group of string sculptures that were collapsible, facilitating their transport back to the United States. Upon installation, they expanded into large-scale pieces.”²⁷ Nicholas Harris remembers: “He had a Chilean helper, Louis, from the barrio of Santiago who helped him execute the hanging string sculptures,” and, “they maintained their friendship for many decades.”²⁸

Participates in the exhibition Escultura 4 at the Universidad Catolica alongside artists three other artists, including Magdalena Suarez (b. 1929).

Contributes to the book of engravings, Cantar de los Cantares de Solomon, Taller 99, Santiago, Chile.

The Onslaught of Puberty, 1960, papier-mâché and twine, 22 inches tall, reproduced in the “New Talent Issue” of Art in America, 1962

1962

Harris is included in the prestigious “New Talent in America” issue of Art in America. The two-page spread includes Garden Hat (1956) and The Onslaught of Puberty (1960), a striking half-length female nude made of papier-mâché and twine. A quote by the artist reads: “I feel that a sculptor makes his comment when he makes a sculpture.” The magazine’s long-running “New Talent” designation, created in 1954, ran in the magazine until 1966, identifying artists in the 1950s and 1960s such as Donald Judd (1928–1994), Helen Frankenthaler (1928–2011), Ellsworth Kelly (1923–2015), and Joan Mitchell (1925–1992).

1963

Cathedral, 1961, woven string with wood pulee and wrapped clay, 98 x 100 x 84 inches

The Bride, 1961, string on wood, 101 x 33 inches

“The idea is startling . . . these forms represent a leap in a new direction.”

Alice Adams, Craft Horizons, 1963

Harris opens a solo exhibition of string sculpture at Poindexter Gallery, featuring his significantly scaled “collapsible monuments.” In her review in Craft Horizons, sculptor, land artist, and influential fiber artist Alice Adams (b. 1930) writes: “Five large constructions made of string stretched around and between one by two wooden frames of different shapes and placements, with the string often used as warp for woven areas. In two of these, approximately twelve-foot tall ‘collapsible monuments,’ the forms are tubular and mostly opaque. More effective, however, are an open forest of black string and a woven, labyrinth, also in black . . . the idea is startling . . . these forms represent a leap in a new direction . . . ”²⁹

Visitors to the exhibition Hans Hofmann and His Students organized by the Museum of Modern

Art, at the Richmond Artists Association, Richmond, Virginia, February 1964, The Museum of

Modern Art Archives © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

The Bride (1961), a slender, vertical string sculpture measuring more than eight feet tall and balloons at either end, is included in a traveling exhibition organized by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Hans Hofmann and His Students.

Moves to Bolinas, California in the fall. In the artist’s 2018 obituary in Point Reyes Light, Jared Bowen reports that, “On a trip to California, the Harrises visited the captain of the USS Ault at his home in Bolinas. Paul immediately took to the place, though Marguerite feared there would be no work in so small and remote a town.”³⁰

Harris sews his first stuffed cloth figure Woman in Blue Slacks. By 1964, he will have produced three additional works, including Woman in Pink Gown (1964) and Woman Giving Her Greeting (1964). “Vivaciously colored, highly patterned,” enthuses Leah Triplett. The body of work, she adds, “demonstrates a painterly sensibility and a command for expressing emotion through material and formal juxtapositions” and “anticipates installation art of the late 1970s and 1980s in their sense of space and scale.”³¹ The sculptures were heavily influenced by available materials. In a 2000 radio interview, he reflects that, “In my time . . . we were faced with new materials which looked like they were going to have great possibilities for us . . . For my part, I couldn’t afford bronze, and I don’t think I had the physical structure for working in stone. I just had to look around because of the problems of money; and when I came to Bolinas, in a house that we rented, someone had had a fire and had left clothes . . . And she left some mattresses. And so I stuffed these and made stuffed figures for quite a while that I sewed . . . It did express something that I needed to say at that point . . . and it helped me to find my subject matter.”³² Nicholas Harris remembers, “After school I would often come to his studio on the Bolinas Lagoon, and I have similar memories of him sewing diligently for hours on end. I remember threading many of his curved needles so he could stay focused on the work. The word got out that he was making these cloth sculptures of women in chairs. Family friends donated furniture and cloth, some of which ended up in the sculptures. Our friends couldn’t believe that a man sewed so well and so much.”³³

Cloth figure sculptures are included in the Smithsonian Institution’s New American Figurative Art, 1963-68. The show travels through several European countries.

1964

Participates in the Arts Council of Philadelphia group exhibition, Dial Y for Sculpture.

Begins teaching at San Francisco Art Institute, where, between Spring 1964 and Spring 1966, he will teach alongside Jay DeFeo (1929–1989), Richard Diebenkorn, Stephen deStabler (1933–2011), Frank Lobdell (1921–2013), Ron Nagle (b. 1939), Manuel Neri (1930–2021), and others.

Builds a two-story home in Bolinas with sons Christopher and Nicholas, and local laborers, on Ocean Parkway with, according to a 2018 obituary, “ a view of the Pacific. There was a kitchen upstairs and a studio below, with a large atelier in the rear where the wooden floors are now covered in layers of splattered wax Paul used to create the positive for bronze castings. Clay originals, plaster molds and oxidizing sculpture litter the yard also abundant with lemon, grapefruit, sour orange and plum trees.”³⁴

A local newspaper reports on Harris, referring to him as “a painter and sculptor of note, and has been called by his New York gallery, the Poindexter, a ‘renaissance man,’ because of his many talents.”³⁵

Serves as Guest Artist at California College of the Arts during the summer session, June 22 to July 31. The teaching appointment includes payment, studio access, and lodging; Meme joins him and sons spend the summer in Montana.

1965

The cloth figures with their outstretched limbs sewn into domestic seating, The Convalescent and Woman Laughing, both 1965, are shown in New Art 1965, a showcase of sixty painters and sculptors in the American Express Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair, curated by Brian O'Doherty (1928–2002), a leading conceptualist and a visual art critic who had previously reviewed for The New York Times, and Wayne Anderson, a professor of history, theory and criticism of art and architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Harris receives solo exhibitions at the Berkeley Gallery, in Berkeley, California and at the Lanyon Gallery in Palo Alto, California.

A selection of his artwork is exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago’s “Society for Contemporary Art Annual Exhibition.”

“Displays an accomplished sense of planar simplification and supple, surface modulation despite the recalcitrant medium he has chosen to work (sew) in . . . The boy sews like an angel.”

Robbert Pincus-Witten, Artforum, 1967

Woman Laughing, 1965, cloth on wood chair, 41 x 36 x 36 inches

Woman in Blue Slacks, 1963, cloth on wood, 50 x 32 x 30 inches

The artist’s studio in Bolinas, undated, Paul Harris Archives

1966

Teaches at the University of California at Berkeley.

Harris is included in the annual survey, 10th Annual Selection for the Society for the Encouragement of Contemporary Art, at the San Francisco Museum of Art (now the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art). Created in 1961, the collecting club made up of museum supporters interested in educating its members, and the public, about the most current art practices exists today. In 1967, the survey would be transformed into the museum’s annual SECA Art Award.³⁶

A trio of sculptures—Dream on a Red Couch (1964), Woman in Pink Gown (1963–64), Woman in Green Gown (1965)—go on view in How the West Was Done at the Art Council of Philadelphia from March 9 to March 31, organized with advice from John Coplans, a founding editorial staffer at Artforum who will later become editor-in-chief. Art critic Dorothy Grafly in The Sunday Bulletin, muses: “ . . . As you enter the show, you find two gals apparently engaged in animated cross-gallery conversation . . . [and] a pink nude is sprawled on a pink overstuffed couch at the end of the room. There is the flavor of a potential Happening with participation of artist and audience in the setup of the figure.”³⁷

Installation views of How the West Was Done, Art Council of Philadelphia, 1966, Paul Harris Archives

Dream on a Red Couch (1964) will go on view again in New Art in Philadelphia at the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania from September 30 to November 11.

Woman Smelling Her Roses (1966) and Woman in Brown Dress (1965) are on view in People Figures at the American Craftsmen’s Council’s Museum of Contemporary Crafts at 29 West 53rd Street in New York City (now the Museum of Arts and Design) from November 19, 1966 to January 8, 1967. In his introduction, Thomas Kyle, the museum’s assistant director, writes, “In the twentieth century, artists who use the human figure have consciously returned to distortion, not to communicate religious or other cultural precepts, but as a means of expressing personal feelings or making an individual statement. Many of the images are tormented and disfigured—grim or satirical—others are witty and humorous. Today there is a whole category of artists about whom it could be said that they have chosen the figure rather than figurative painting as the medium for their psychological observations and social commentary.”³⁸

Opens a solo exhibition of ten fabric and cloth sculptures on December 20 at Poindexter Gallery in New York City. In an undated letter prior to installation to Ellie Poindexter and Harold “Hal” Fondren, the assistant gallery director, he writes: “I don’t know how to draw, but here is a possible arrangement with due consideration to color, height, and friendships among the ladies.”³⁹ In the March 1967 issue of Artforum, Robert Pincus-Witten will remark, “Paul Harris, in these large stitched and stuffed dolls executed between 1964 and 1966, displays an accomplished sense of planar simplification and supple, surface modulation despite the recalcitrant medium he has chosen to work (sew) in. His figures, for all their evidently Pop-ish afflictions—particularly their Vegas color and floral splotches—achieve a kind of distinguished solemnity. Harris is really an equestrian sculptor who has replaced the horse with the chair—circular rattans, wicker seats and chaise lounges. The figures meld into a comfy upholstered world as distant from the slick ingratiations of Frank Gallo as from the neutral, philosophical presences of George Segal . . . Harris, quite unlike Segal, adores sensuously affronting color . . . The boy sews like an angel.”⁴⁰

A 1966 letter from Paul Harris to Ellie Poindexter and Harold “Hal” Fondren, Archives of American Art

Harris is included that year in The Work of Visiting Artists at the Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore; and is meant to be in Stuffed Expressionism, Abstract Inflationism, a group show at Graham Gallery in New York City that included Eva Hesse (1936–1970) and is reviewed in Artforum, but the work does not arrive.⁴¹

1967

Arranged on a raised platform, Woman in Green Gown (1965), Woman Smelling Her Roses

(1966), Woman Giving Her Greeting (1965), and Woman Laughing (1964) go on view in the ambitious and touring survey, American Sculpture of the Sixties, alongside artists such as Ellsworth Kelly, Donald Judd, John McCracken (1934–2011), and Claes Oldenburg (1929–2022). Organized by Maurice Tuchman of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the exhibition is on view in Los Angeles from April 28 to June 25 and at the Philadelphia Museum of Art from September 25 to October 29. In his introduction, Tuchman remarks on Harris’s “sewn and stuff personages” as effigies . . . poignant as they are terrifying.” In an essay in the exhibition catalogue on Dadaist tendencies among contemporary sculptors, James Monte, an American art critic and associate editor at Artforum, writes: “Paul Harris, another of the sculptors chosen for the exhibition, remains difficult to characterize in the normal, ‘he-comes-out-of-so-and-so; or such-and-such a tradition.’ When his upholstered women emerge from their upholstered plinth chairs the viewer experiences a jerky, visual dislocation. The chintz material used to cover the figures and the chairs unifies each piece as an ensemble. Usually Harris paints the various segments of chairs, limbs, clothing, shoes, etc., to give the viewer a better opportunity to differentiate between them. In so doing, he deliberately permits a certain feckless nonchalance to permeate the finished pieces. By grouping four or five pieces together, a tableau effect is created making one acutely aware of the multiplicity of levels on which Harris’ work affects the onlooker.”

Installation view of American Sculpture of the Sixties, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1967, Paul Harris Archives

“His sewn and stuff personages . . . are as poignant as they are terrifying.”

Maurice Tuchman, American Sculpture of the Sixties, 1967

Harris is included in a selection of American artists including Roy Lichtenstein (1923–1997), Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), James Rosenquist (1933–2017), Wayne Thiebaud (1920–2021), and Andy Warhol (1928–1987) chosen by William C. Seitz, the director of the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University, as part of the high profile, visually dazzling IX Bienal de Sao Paulo, Brazil, on view from September 22 to December 8. Art critic Hilton Kramer, writing in The New York Times, enthuses that the “exhibition of American pop art in the ninth Bienal de São Paulo, which opens officially on Friday, is clearly going to be the sensation of this huge exposition of contemporary art representing 60 countries. Called ‘Environment USA: 1957-1967,’ and given a spectacular installation, the show is already the focus of much discussion, envy and consternation.”⁴²

Harris begins teaching at Sacramento State College. A suite of crayon and pastel drawings go on view at Adeliza McHugh’s two-room Candy Store Gallery in nearby Folsom, in which she displayed, and sold, paintings and sculptures by artists who would eventually become nationally and even internationally significant, such as Robert Arneson (1930–1992), Roy De Forest (1930–2007), and David Gilhooly (1943–2013). In his review in Art Views, “Descendant Of Cezanne: Paul Harris’ Pastels Echo Master’s Technique And Vision,” Charles Johnson writes that, “With Harris’ [sic] pastels, it is hard not to think about Cezanne, partly because there is the same kind of diagonal stroking that Cezanne used in his paintings. But Harris’ strokes are longer, less dense, and as pastel will do, allow other colors to show through from underneath . . . Another paradox is provided by Harris’ practice of clouding over some parts of a picture. This is a natural function of powdery pastel, but Harris enhances it occasionally with a gentle smudging here and there. The paradox is that despite this misty feeling, colors are not necessarily muted, and often come out with a wonderful richness, especially where his delicate hatching builds up hue on hue.”⁴³

Receives the prestigious Neallie Sullivan Award from the San Francisco Art Institute, later known as the Adaline Kent Award. The award, according to Jeff Gunderson of the SFAI Legacy Foundation and Archive, “honored California artists with an exhibition at SFAI and an honorarium” and “began in 1959 with Manuel Neri.”⁴⁴

1968

Harris begins teaching in the sculpture and design departments at California College of Arts and Crafts (CCAC) in Oakland, California, following a recommendation from Richard Diebenkorn, who taught at the school a decade earlier. The school was founded in 1907 to provide an education for artists and designers that would integrate both theory and practice. Harris arrives at a moment of growth and change at the college, which had recently attracted Viola Frey (1933–2004), and who with Peter Volkous (1924–2002) and Robert Arneson, had helped to bring bring international prestige to the ceramics department and instigated that decade’s ceramics revolution. He will teach at CCAC until 1992, becoming a beloved instructor and mentor.

Harris’s still life bronze Six Bottles (1965) is included in the Crocker Art Gallery’s (now the Crocker Art Museum) biennial 1968 Invitational West Coast ’68 Painters & Sculptors in Sacramento, California, from September 1 to October 6.

Harris is shown at Prospect ‘68: International Preview of the Art in the Galleries of the Avant-garde at the newly opened Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, Germany. In 1970, he will receive a solo exhibition with the gallery.

1969

Harris receives a solo exhibition of sculpture at William Sawyer Gallery in San Francisco, on view from January 6 to February 6.

Exhibition poster, William Sawyer Gallery, 1969

Woman in Blue Slacks (1963) goes on view in Soft Art organized by Ralph Pomeroy at the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton from March 1 to April 27. In an essay accompanying the show, Pomeroy, a champion of soft sculpture and an editor at ARTnews and Arts⁴⁵, writes: “In almost every work the color—and there is quite a lot of it—is not applied but selected, being a part of the material chosen. In Richard Tuttle’s case the canvas is dyed by him. But the great felt swags of Robert Morris; the pale dacron tints of Keith Sonnier; the bright patchwork of Paul Harris’ stuffed figures, or the almost invisible machine-stitched thread in Alan Shields’ pieces, all get their coloring from the material itself.”⁴⁶ Remarking on the artist’s early stuffed work, curator and critic Leah Triplett observes that “A singular woman sits on a chair striped with blue, grey, black, and white. Her legs are crossed at the knees, and her arms rest on her lap and to her side, respectively. The titular woman is lifelike in both gesture and form. Nevertheless, a certain absurd roundness pervades her body, melding her into the similar fullness of her chair. Her upturned face, raised in attention as if she's just been called to, is disturbingly blank.”⁴⁷

Receives a ninety-day Tamarind Institute of Lithography fellowship in Los Angeles, California, and, under the supervision of Master Printer Serge Lozingot, completes The Shut-In Suite, twenty-one lithographs in black tusche and crayon. In a 1976 interview with Los Angeles County Museum of Art curator Maurice Tuchman for the Archives of American Art on the occasion of Richard Diebenkorn, Harris says of the residency, “When I was working at Tamarind, I invited Dick to come there . . . I had been there a couple of months, three months, and I was about out of my head . . . I had a fight with the proprietor [June Wayne] . . . I took off . . . I couldn’t stand it anymore . . . I arrive back at the last day . . . and Dick came out, to say, ‘well everyone is waiting for you.’ But he was very shy and was trying to tell me that inside there was a lot of tension when I would arrive . . . And it was the kind of thing that he hopes won’t happen, but it was also kind of exciting to them . . . when things don't go smoothly. When people have shown their sharp edges. . . .”⁴⁸

In November, an exhibition of the material opens. The promotional text reads, “A shut-in’s intimate reflections on his environment. Harris’ [sic] crisp images appear as still lifes seen through a zoom lens: the views are cropped and flattened . . . The combination of flat patterns and implied dimension causes each work to shift between an abstract and a representational identity. This quality is strong in ‘Lawn Party’ where the image is flat grassy green topped by broad green and white stripes suggesting the corner of an awning. In another, ‘Rain’ (printed on yellow vinyl) red and blue floral wallpaper delineates a hanging raincoat.”

Rain, 1969, lithograph, 30 x 22 inches

Lawn Party, 1969, lithograph, 30 x 22 inches

-

²⁴Lawrence Campbell, review of Paul Harris, ARTnews, October, 1960.).

²⁵Stuart Preston, “Full Speed in All Directions,” The New York Times, September, 25, 1960.

²⁶“Noted Artist Opens School,” Pacific Sun, January 1, 1964.

²⁷Morris Yarowsky, foreword to Paul Harris Drawings, (University of Washington Press, Seattle & London, 1996).

²⁸Christopher Harris, e-mail interview with the author, 2025

²⁹Alice Adams, review of Paul Harris, Craft Horizons, Vol. 33, Issue 38, (May, 1963).

³⁰Jared Bowen, “Paul Harris in Bolinas, harnessed power in art,” Point Reyes Light, June 6, 2018.

³¹Leah Triplett, biography of Paul Harris, 2025.

³²Paul Harris, interview by Carrie Adney.

³³Nicholas Harris, email interview with the author, August 1, 2025.

³⁴Bowen, “Paul Harris in Bolinas, harnessed power in art.”

³⁵“Noted Artist Opens School,” Pacific Sun, January 9, 1964.

³⁶“SFMOMA Marks 50 Years of Engaging San Francisco Bay Area Artists,” (press release), October 5, 2011.

³⁷Dorothy Grafly, “Pop Sweeps Our Way From Across the Divide,” The Sunday Bulletin, March 13, 1966

³⁸Thomas Kyle, foreword to People Figures, (New York: American Craftsmen’s Council’s Museum of Contemporary Crafts, 1966)

³⁹Paul Harris, letter to Ellie Poindexter and Harold Fondren, 1966, Archives of American Art

⁴⁰Robert Pincus-Witten, review of Paul Harris, Artforum, Vol. 5, No. 7, March 1967

⁴¹Robert Pincus-Witten, review of “Abstract Inflationists and Stuffed Expressionists,” Artforum, Vol. 9, No. 4, May 1966.

⁴²Hilton Kramer, “Art: United States’ Exhibition Dominates Sao Paulo's 9th Bienal; 45 Big Pop Pieces in ‘Environment USA’,” New York Times, September 20, 1967.

⁴³Charles Johnson, review of Paul Harris, Art Views,

n.d.

⁴⁴Jeff Gunderson, “1963 Bruce Conner, Adaline Kent, Nealie Sullivan, Jerry Burchard, Jeff Gunderson from E-mail Archive,” SF Arts Alumni, https://www.sfartistsalumni.org/jeff-gunderson-s-email-archive-details/sfai-1963-bruce-conner-adaline-kent-nealie-sullivan/r/recHnxXR69s4VFMen

⁴⁵Edward Field, “Remembering Ralph Pomeroy,” The Gay and Lesbian Review, Vol. 7, Issue 3, Summer 2000.

⁴⁶Ralph Pomeroy, “Introduction,” Soft Art, New Jersey State Museum, Trenton, New Jersey,1969.

⁴⁷Triplett, “Paul Harris: Interior Interests.”

⁴⁸Paul Harris, interview by Tuchman.