1950s

1950

Returns to the University of New Mexico. Receives B.A. in Fine Arts. Agnes Martin (1912–2004) is a classmate. Of her works on paper and paintings at the time, Harris would in 1976 remark that “Aggie had a lot of force.”¹⁷

Meets Richard Diebenkorn (1922–1993), a fellow student. The two artists and their wives form rich, lifelong friendships. Diebenkorn will eventually become “perhaps his closest friend.”¹⁸

Serves as a graduate teaching assistant at the University of New Mexico. Participates in a group exhibition, Six Young Artists, at the Jonson Gallery, University of New Mexico.

Marries Marguerite Kirk on June 3 in Beaver, Pennsylvania.

Paul and Meme on the campus of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1950, Paul Harris Archives

Paul and Meme [seated, at right] with friends in the Sandia Mountains, New Mexico, 1950, Paul Harris Archives

Paul Harris and Marguerite Kirk, Beaver, Pennsylvania, 1950, Paul Harris Archives

1951

Receives his M.A. in Painting and Sculpture at the University of New Mexico.

Son Christopher is born in Albuquerque, New Mexico on July 6. Moves with wife and son to Gallup, New Mexico. Participates in a group exhibit, Three Sculptors, Three Painters at the Albuquerque Public Library.

1952

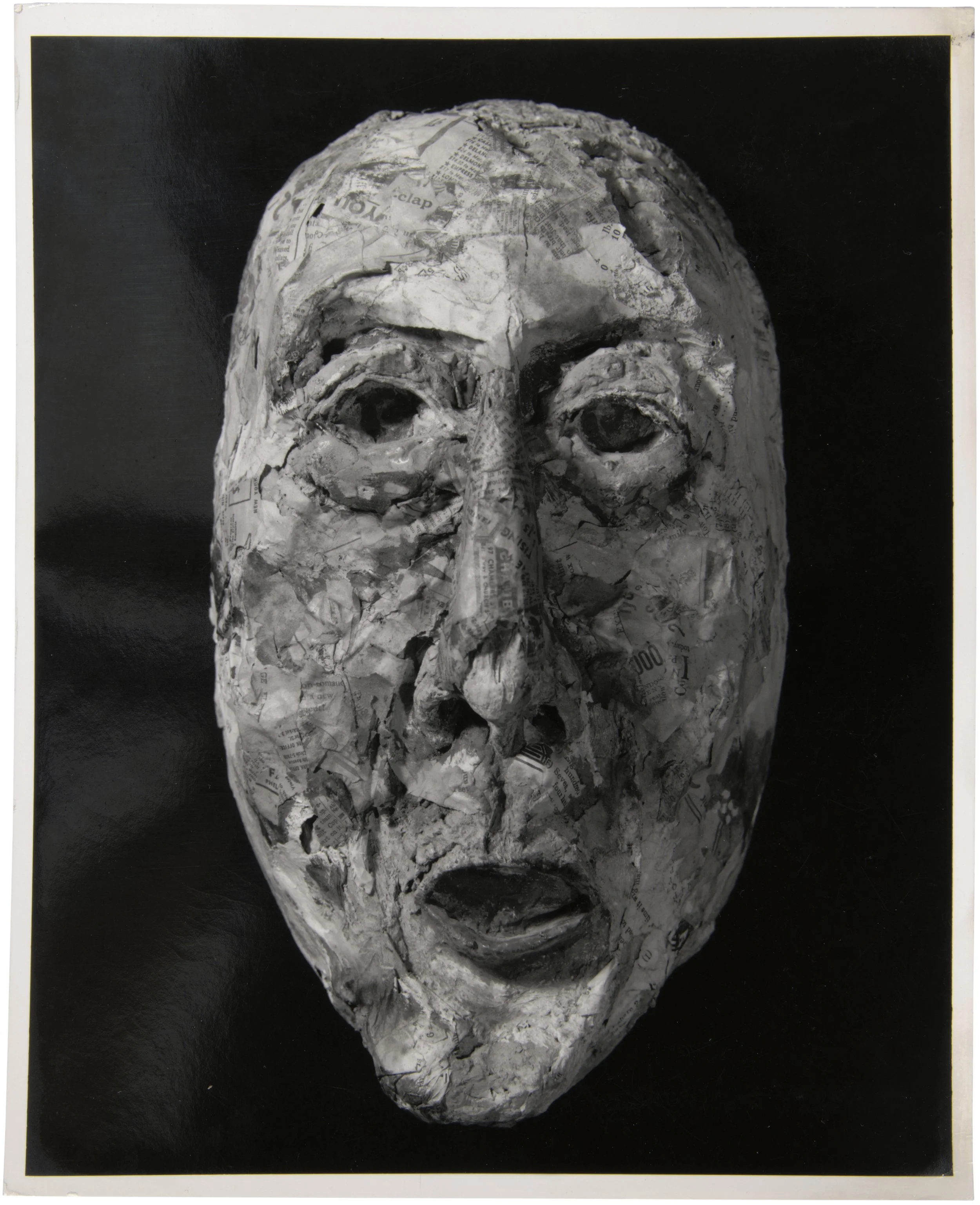

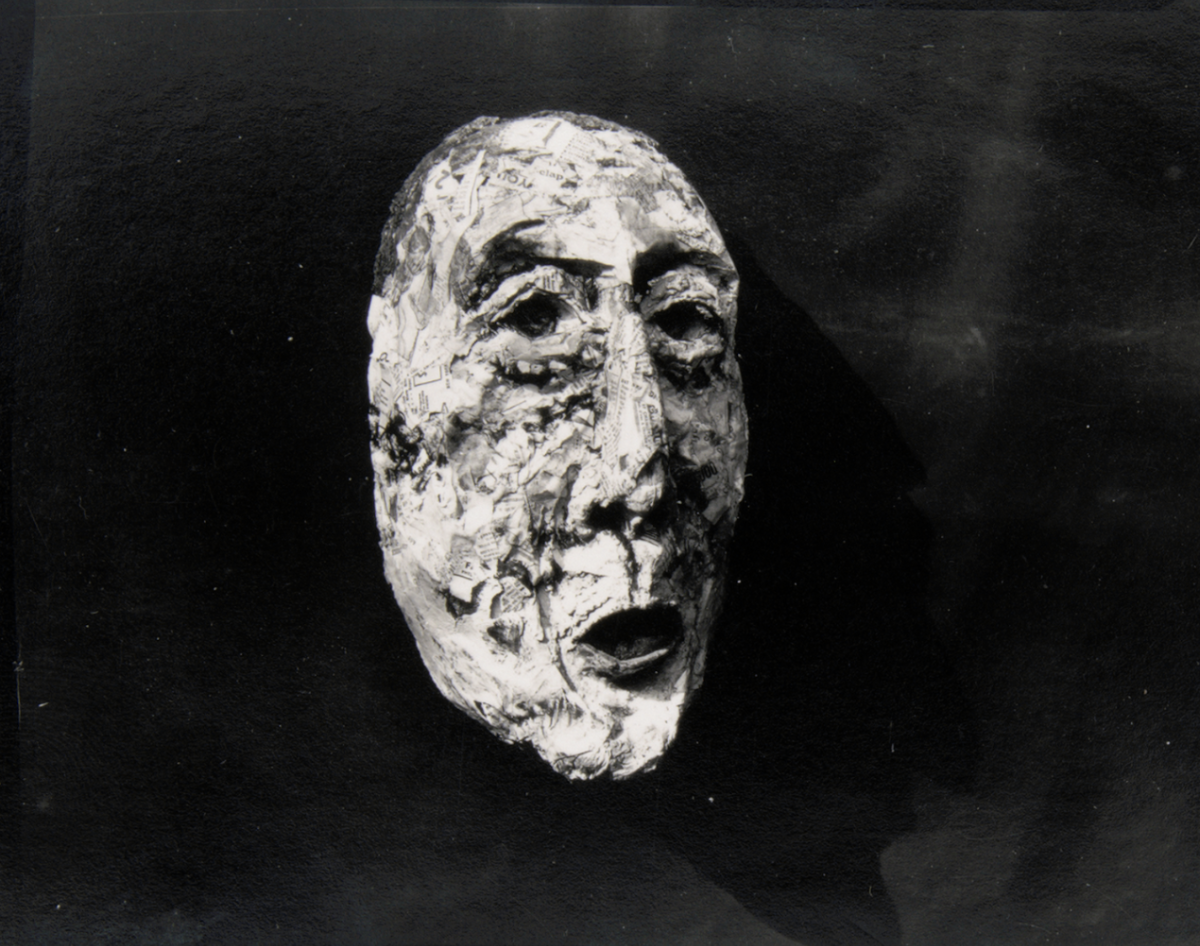

Moves with his family to Jamaica, British West Indies where he begins his teaching career at the Quaker School in Highgate and later at Knox College, Sepalding, Jamaica. “Although Harris’ artwork creativity expanded in Jamaica, particularly his series of masks, including British Playwright and Dramatist,” Christopher Harris remembers, “the family's shaky finances were aided by loans and gifts from Meme’s family. For Harris this was intolerable, and the family moved back to the United States.”¹⁹

In a radio interview in 2000, Harris will say of the impulse to live and work in Jamaica, “We just wanted to get out of this country as a protest . . . On the faculty there were a number of people who were anti-war and it was a Korean War time. And I shared that feeling. One war had shown me that the second war wasn't going to be another, good thing to do. And so we went to Jamaica where we could, I guess make a presence for, a witness maybe, for . . . peace.”²⁰

1954

British Playwright and Dramatist, 1953, papier-mâché, rope, and putty, 16 x 9 x 7 inches

Participates in a group show, Artists in the Island, at the Institute of Jamaica, Kingston.

Begins working actively in papier-mâché, newspaper, plaster, and fiber (such as rope and fur) to produce a series of fantastical wall mounted masks; by 1954, he will return to experimenting with concrete. In a 1958 feature by Elenore Lester in the Newark Star-Ledger, Paul Harris will say,

“I was teaching at Knox College in Jamaica. We were short of materials, so I had the students tear up some of their old drawings, dip the strips in glue and press them together to make papier mache. We made our own glue with flour. Working with the students to make masks, I finally decided to try some of my own.”

Jessica Holmes, art critic and former deputy director of the Calder Foundation, argues that “though not strictly autobiographical, the work he made in papier-mâché throughout the 1950s references his experiences of the previous decade. Many of these early sculptures were masks, a subject that held great significance for a wide range of artists in the first half of the twentieth century. Notably, Picasso studied masks of the African tradition in depth as he worked towards his Cubist breakthrough, and masks were also a trope that deeply influenced the Surrealists. As a response to the horrors of war, as well as their allusive references to dreams and nightmares, visions, and netherworlds, masks were likewise a potent symbol for Harris and other artists of his generation.”

1954

Harris’s son, Nicholas, is born in Papine, St. Andrew, Jamaica on July 27. The family soon returns to the United States.

In a vivid, affectionate letter in response to drawings Harris produced in Jamaica, Elaine de Kooning writes: “I was surprised by the drawings in terms of your Ptown abstractions which were so stern—protestant—puritanical. So I naturally feel closer to the drawings since they are so full of social comments. There was one with a woman's figure lying on a bed—a peculiar sort of collage—that I thought was magnificent. For some reason or other, when those little pieces of paper are painted on and you paint or draw over them, the painting is made sharper or more unpredictable, I don’t know exactly what, but the indirectio-ness? [sic] helps . . . Then I liked the portraits that were horizontally faceted . . . There were no features left and still the faces were very clear. It would be wonderful if you could do the same thing in painting. Then I loved the flippant little contour drawings of you having tea with various eager ladies . . . ”

1955

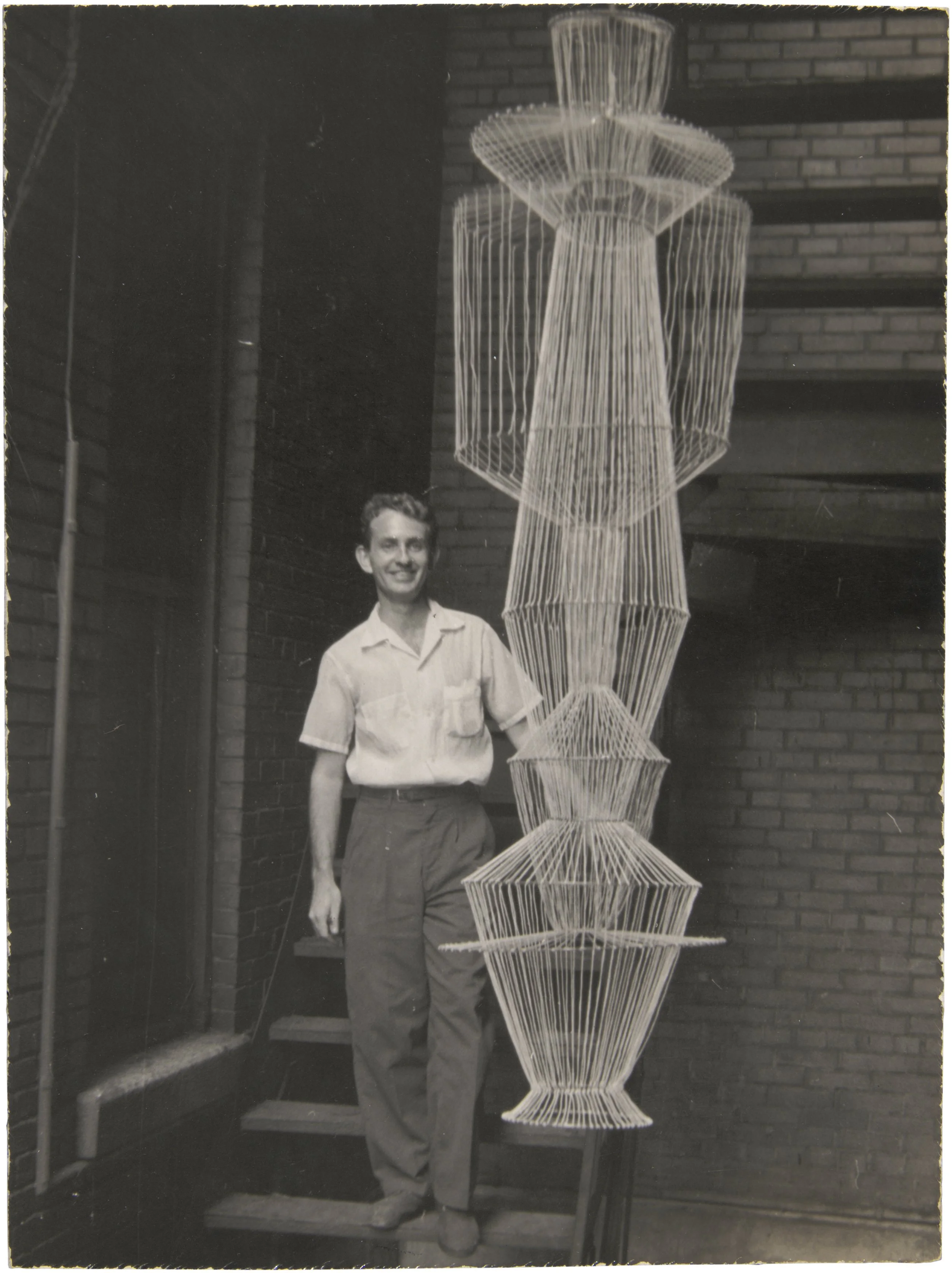

Harris begins working in string, a lightweight, dynamic mode and milieu he will continue until 1962 and may have been a creative extension of a loom he used in the family home in New Jersey.²¹ This period marks the beginning of his use, later seen in his cloth and fabric sculptures, of non-traditional sculptural materials. Curator and critic Leah Triplett, whose curatorial practice looks at the ways in which contemporary and historical artists incorporate soft materials to offer novel ways of merging material with expression, argues that “as critics grappled with the aesthetics and range of materials used by postmodernist sculptors, Harris—himself a postmodernist who wove wit, playfulness, and illusion into his work—continued to exploit the emotional possibilities of softness. For this, he was among a vanguard of artists across the U.S. manipulating fabric, string, and batting through deskilled or sophisticated needlework and weaving.”²² Produces his first “collapsible monument,” Instrument and Strings (1955), a volumetric eight-foot-tall sculpture made with string and metal hoops suspended from the ceiling.

Harris with Instrument and Strings (1955)

1956

Receives a Doctor of Education in Teaching Fine Arts from Teachers College, Columbia University. He is the recipient of the Arthur Wesley Dow Scholarship Fund, named after the artist and passionate champion (1857–1922) of the American Arts and Crafts movement, and the Naomi Norsworthy Memorial Fund.

Begins working as an Editorial Associate for ARTnews, a position he will hold until 1956, under Executive Editor Thomas Hess, a champion of the first generation of Abstract Expressionism. His fellow reviewers include the painter Fairfield Porter (1907–1975) and writer and poet Frank O’Hara (1926–1966). His reviews are crisp, descriptive, and economical.

Reviews the inaugural show of Poindexter Gallery, which included two abstractions by Richard Diebenkorn, and was temporarily located in the home of Elinor “Ellie” Poindexter at 141 East 36th Street in New York City. In an interview in 1976, he will remember: “The only thing in the show I was interested in was the Diebenkorns . . . she had some guests from out of town who were being fed lavishly. And I was sitting outside, and they were bringing me martinis . . . I hadn’t eaten, and I got wildly drunk. And finally . . . I am allowed to go into the dining room where most of the show was hung. I knew I was uncontrollably drunk, and I just had to get out of there. I said goodnight to Mrs. Poindexter and went to leave, and I looked at this enormous glass door that she had in her lavish apartment . . . I didn’t realize there was a little table behind the door. And so I swung this glass door back . . . It hit the table and it just broke . . . I must have been like Charlie Chapin walking out into the air pretending this thing had never happened.”

1957

Appointed Assistant Professor of Art, State University of New York at New Paltz.

Writes “An Introduction to the Painting of Johannes Molzahn” for ARTnews

1958

In a spring 1958 letter to Richard Diebenkorn, Ellie Poindexter writes: “I got hold of Paul Harris, and we are giving him a show with another sculptor in May. His work is very interesting.” Poindexter, who represented Diebenkorn, Willem de Kooning (1904–1997), Franz Kline (1910–1962), and Milton Resnick (1917–2004), will show Harris until 1970.

Opens his first solo exhibition with Poindexter Gallery, on view from May 19 to June 6 at 21 West 56th Street alongside the British sculptor Mary Frank (b. 1933)—his first in New York City. A reviewer in Arts remarks: “With a certain specific, contemporary anecdote in mind, Paul Harris molds papier-mache into a sturdy, critical, witty series of nine masks . . . Patriot glitters in glaucous, snowy enamel, triumphantly coifed in yellow-white hair, her sightless socketed eyes ready to ferret out subversion, the oval, lipless mouth continually in chatter, wherein is seen her triumphant red, white and blue tongue.”

Departs from papier-mâché as a material, “turning to other media he probably considered more sophisticated,” argues Holmes. “Between 1958 and 1960, Harris leaned into his sculpture in these media, which offered a plasticity akin to that of papier-mâché but were more historically aligned with the fine arts. Torso II (1958), one of his first fully developed concrete works, was made from a papier-mâché cast titled Torso I, though he later used plaster for these purposes.”²³

Patriot, 1954, papier-mâché and fur, 14 x 11 x 6.5 inches

Installation of Poindexter Gallery show, 1958, Paul Harris Archives

1959

Garden Hat (1956), a smiling, nearly four-foot-tall papier-mâché on board, is included in Recent Sculpture, U.S.A. at the Museum of Modern Art from May 13 to August 16 in New York City alongside work by Alexander Calder (1898–1976), John Chamberlain (1927–2011), and David Smith (1906–1965). A. L. Channin, writing on the survey in The New York Times, remarks: “Since the war America has witnessed a phenomenal upsurge of sculpture. As startling as the constant output of new works are the unorthodox ideas they express.”

A work goes on view in New Forms-New Media II at Martha Jackson Gallery, New York.

Installation view of the exhibition, Recent Sculpture U.S.A., May 13, 1959-August 16, 1959, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Photographer: Soichi Sunami, Photographic Archive, The Museum of Modern Art Archive © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Garden Hat, 1956, papier-mâché on board, 45 x 25 inches

-

¹⁷Harris, interview by Tuchman.

¹⁸Christopher Harris, e-mail interview with the author, 2025.

¹⁹Christopher Harris, e-mail interview with the author, 2025.

²⁰Paul Harris, interview by Carrie Adney.

²¹Nicholas Harris, e-mail interview with the author, 2025.

²²Triplett, “Paul Harris: Interior Interests.”

²³Jessica Holmes, “Paul Harris: Sculpture,” 2025.