Uncanny, or Erotic:

Paul Harris Bronzes

by Jessica Holmes

In his interdisciplinary practice, there seemed to be no material too formidable for Paul Harris (1925–2018) to surmount.

Though his fabric sculptures may be his best known body of work, the artist was equally adept with bronze, with which he worked regularly from the 1960s onward, in step with other midcentury artists like Jim Dine and Nancy Graves who took cues from a previous generation of sculptors such as Henry Moore and Alberto Giacometti, expanding the possibilities of what was regarded as a classical medium. From this more muscular, firm matter—so unlike cloth—he was nonetheless able to tease out a parallel eroticism that evidences a profound engagement with form.

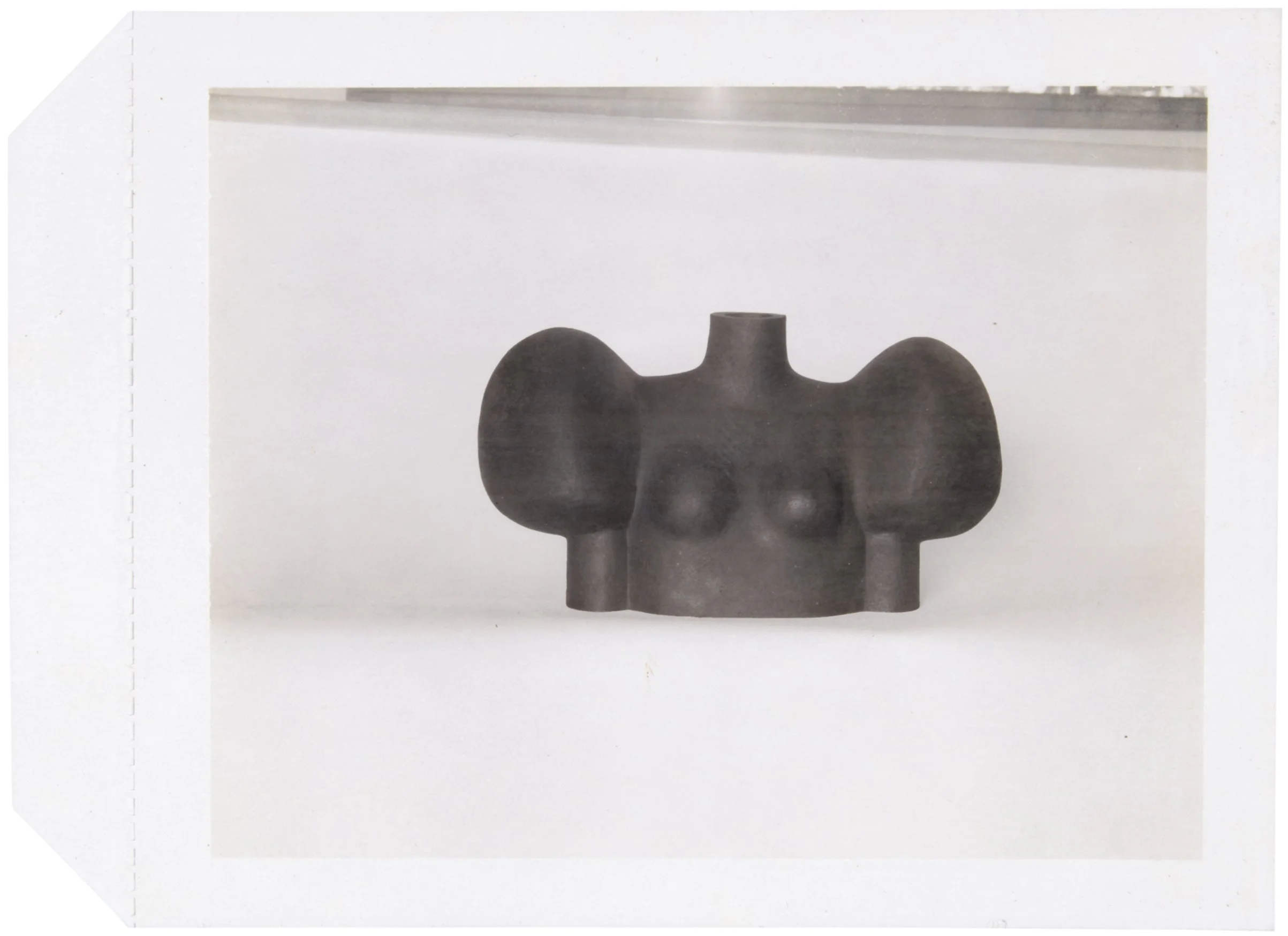

Studio photograph of Anna Turning (1989), c. 1989, Paul Harris Archives

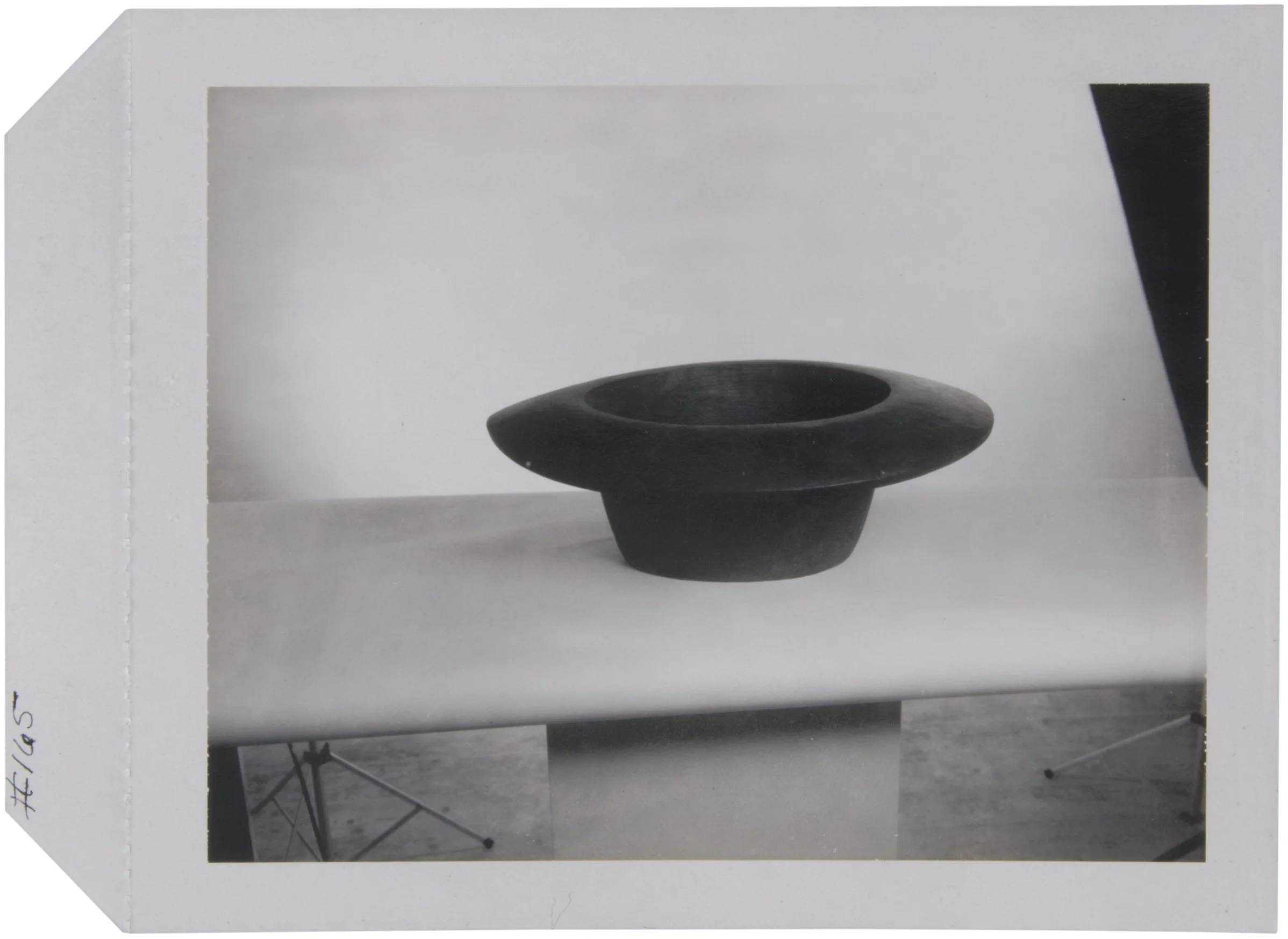

In treatments of the female body, this carnality emerged in sometimes surprising ways. Art historian Leah Triplett notes the “almost cartoonish” proportions of the swell and scale of Harris’s fabric sculptures of women; these deliberately unbalanced dimensions also play into Harris’s bronzes. In Woman Bending Over (1978), Harris has crafted the bronze so that the eponymous woman bends at the waist at a steep angle, her buttocks thrust into the air. Her head and torso are in disproportion to her long legs, which end in oversized feet that help counter instability. The work is frankly, playfully sexual in subject but simultaneously exhibits a more subtle physicality in its fluid curves and soft lines. A decade later, in works like Anna in Love (1987) and Anna Turning (1989), Harris pared down his subject to only a torso and a pair of legs, bent at the knee and spread apart in the former, and gracefully crisscrossed in the latter. The duo is a masterclass of form in bronze, with Harris reducing the body to essentials in an almost minimalistic approach that yet conveys so much. The legs and torsos are nearly abstracted to curvilinear shapes, but retain an inherent tender and humanistic quality. These two works were both cast at the acclaimed Shidoni Foundry in Tesuque, New Mexico, as was another treatment of the female body he made a few years later, Woman With Puffed Sleeves (1992), which saw Harris once again pivot towards humor. Here, a pair of female breasts is minimized by a pair of outsized shoulders, presumably enhanced by the puffed sleeves of the title. That Harris chose to focus on the upper arms—typically a body part with far less sexual connotation than the breasts—he mischievously subverts preconceived notions of the erotic.

Polaroid and drawings of Woman with Puffed Sleeves (1992), c. 1992, Paul Harris Archives

In his bronze sculptures, process was paramount for Harris. He often began with a wax model, a substance that preserved the marks of the artist’s hands when transferred to the alloy. His surfaces in these works thus capture distinct moments in time and retain a remarkable sense of immediacy. Harris’s ability to imbue the material with such a sense of vitality is immediately palpable in one’s own body when in communion with one of his works. Wax was a material that clearly brought Harris tactile and aesthetic pleasure; aside from the casting process, he also worked in wax crayon throughout his life. Its pliability allowed for wide-ranging experimentation and allowed for the preservation of the artist’s hand upon the work, a reinforcement of the apprehension of time.

At the heart of this process was an ongoing meditation on transformation. As the wax model was converted to bronze, so too were Harris’s eclectic and varied choices in subject matter. Tea kettles and visages, torsos and jaunty hats—all were possibilities for veneration in bronze. His famed sense of humor was frequently suffused with profundity rather than whimsy, as a work like Balanchine’s Kitchen (1985) telegraphs. Here, renderings of a wooden kitchen spoon, an overturned drinking cup, and a teapot are elegantly positioned, with the three items all seeming to balance together in harmony. The handle of the spoon rests atop the cup, while the spout of the teapot abuts it from the other side. The humble kitchen articles hang together in a balletic arabesque. And though they are inanimate objects, Harris graces them with a corporeality that relates to the bronze body figures. In the angles and shapes of Balanchine’s Kitchen, one might also recall Harris’s masterful work Woman Lying Down (1972), a nude female torso in face-down repose. As if she has just collapsed onto a bed, the figure’s legs are articulated, cocked at the knee in casual akimbo. Harris’s acute observation of the mortal form is on full display as he elevates this blithe gesture—so relatable, so human—to poetic transcendence.

Studio photograph of Gallon Jug and Others (1967), c. 1967, Paul Harris Archives