Novel Experimentation,

Conceptual Freedom

by Jessica Holmes

By refusing to limit himself, Paul Harris (1925–2018) amassed a body of work rare in its physical heterogeneity across the whole of his career.

Though he regularly returned to materials like fabric, string, and bronze, Harris also developed intriguing series of sculpture in other media, including plaster, concrete, wood, and papier-mâché. Such diverse materials often took his work in surprising directions, allowing him novel experimentation and conceptual freedom.

Installation of Poindexter Gallery show, 1958, Paul Harris Archives

The 1940s had been an active, turbulent period in Harris’s life. He’d joined the US Navy upon graduation from high school and saw combat in the Pacific theater aboard the USS Ault. Discharged in 1946 after suffering a serious illness, Harris then traveled to Latin America, where he hitchhiked through Mexico and Guatemala, and was briefly jailed in the latter for vagrancy. After returning to America, he earned degrees in Fine Arts at the University of New Mexico in 1950 and 1951, respectively. As Harris was finding his footing as an artist over the next ten years, he frequently returned to papier-mâché. A number of well-received and reviewed commercial exhibitions in the late 1950s and early 1960s, where sculptures in this medium featured prominently, as well as inclusion in group exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Universidad Catolica in Santiago, Chile, and the Arts Council of Philadelphia, among others, garnered him early success.

Patriot, 1954, papier-mâché and fur, 14 x 11 x 6.5, Paul Harris Archives

British Playwright and Dramatist, 1953, papier-mâché, rope, and putty, 16 x 9 x 7 inches

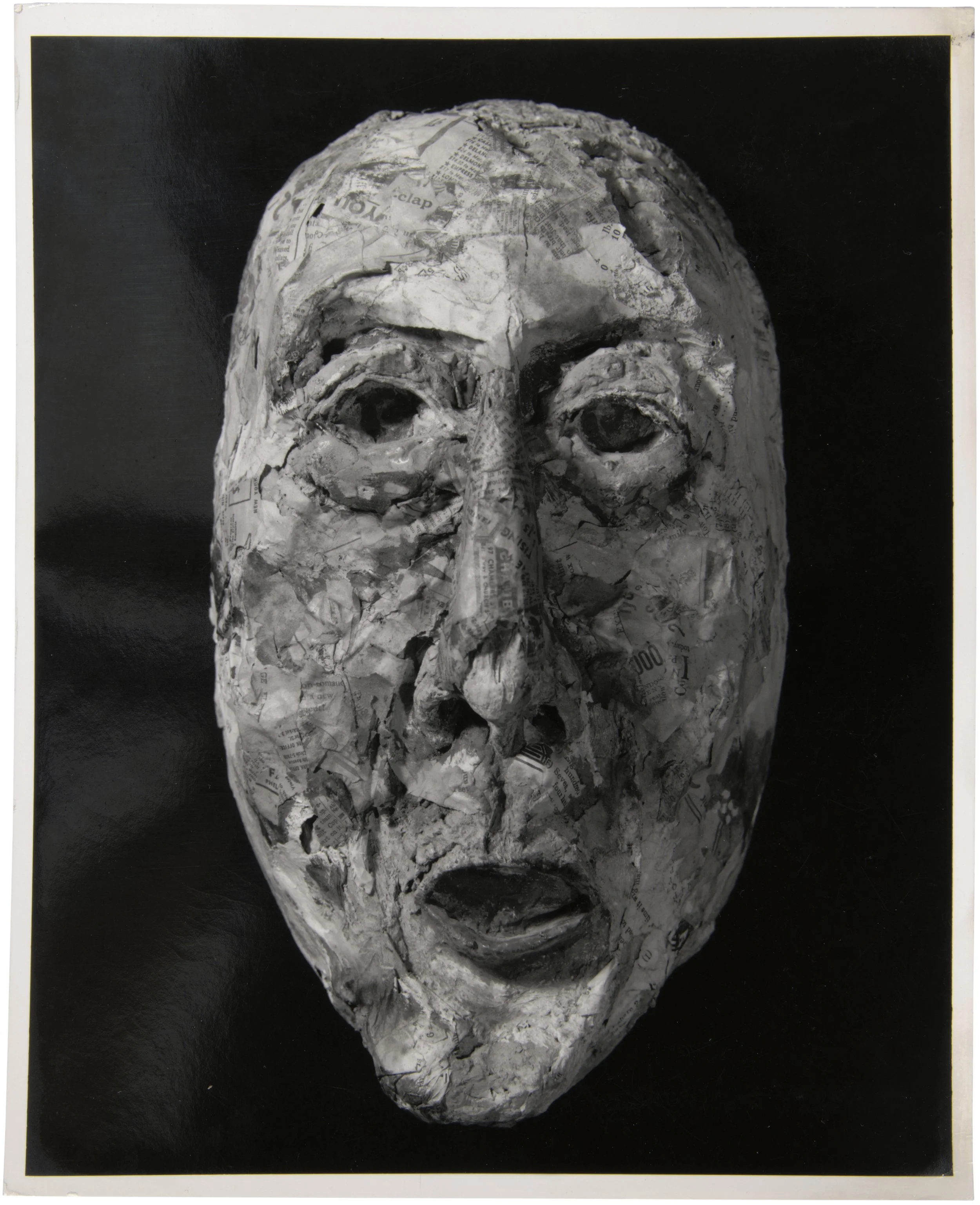

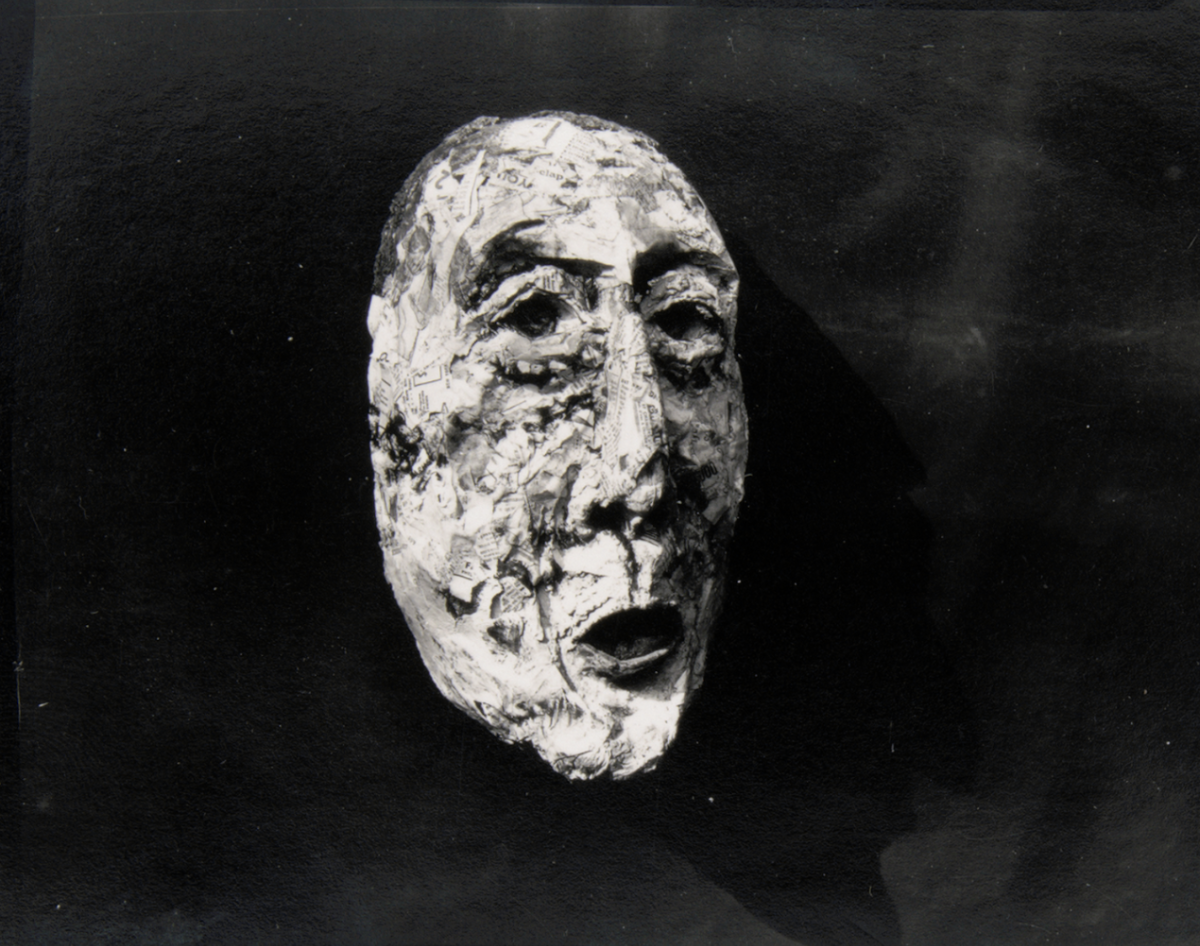

Though not strictly autobiographical, the work he made in papier-mâché throughout the 1950s references his experiences of the previous decade. Many of these early sculptures were masks, a subject that held great significance for a wide range of artists in the first half of the twentieth century. Notably, Picasso studied masks of the African tradition in depth as he worked towards his Cubist breakthrough, and masks were also a trope that deeply influenced the Surrealists. As a response to the horrors of war, as well as their allusive references to dreams and nightmares, visions, and netherworlds, masks were likewise a potent symbol for Harris and other artists of his generation, who explored the form in diverse materials. In California, for instance, Ruth Asawa had a side practice making masks in clay of her friends and contemporaries for thirty years, alongside her better-known sculptural practice. And in the Midwest, photographer Eugene Meatyard made a series of uncanny images of his children wearing misshapen and outlandish masks over their faces, transforming them into unrecognizable specters.

Harris was likely also exposed to the vibrant artistic traditions of the Indigenous societies among whom he traveled and lived in Latin America, Jamaica, and the American Southwest. In fact, he developed his first masks while teaching at Knox College in Jamaica. After assigning his students a papier-mâché project where they began to form masks, he decided to make some of his own.

A 1958 article on Harris in the Newark Star Ledger quotes an unnamed critic who shrewdly observed that the artist’s masks revealed both “the social self and the individual behind the mask.”

Mary Jane as I Knew Her, 1958, painted papier-mâché,

29 x 14 x 12 inches

The faces he depicted are manifold, with many, like Child’s Face or Woman With Cancer (both 1953), exhibiting mottled, grotesque visages. A notable exception is Harris’s work White Man I (1953), where the papier-mâché is smoothed of its natural irregularities, and carefully painted, the eyes, lips, and swoop of hair across the forehead outlined in black. Harris returned to this piece in the late 1960s when he made a series of works in plexiglass, vacuum-formed and then hand-painted. (Though he is rarely mentioned among them, California Light and Space artists such as Craig Kauffman, Doug Wheeler, and John McCracken were tackling similar techniques with plastic and Plexiglas at precisely the same time as Harris.) Another turning point in these early sculptures is the satirical Mary Jane As I Knew Her (1958), a papier-mâché pair of women’s legs wearing a skirt and pumps, which is meant to be installed hanging from a ceiling. For many years his gallerist Ellie Poindexter, who helmed the Poindexter Gallery in New York and gave Harris a number of shows in the late 1950s and early 1960s, had it hanging over her desk. The work shows his skillful use of the medium, and prefigures Harris’s more widely known fabric sculptures of the female form, which he would begin developing in earnest during the 1960s. An investigation into perception is another facet of Mary Jane As I Knew Her. A photograph of the piece in the Paul Harris archives is inscribed “a child’s view of an adult world,” an indication that Harris recalled that feeling of early childhood, when one is so small that the adults in the room seem like giants, and with this sculpture consciously—and sympathetically—translated that impression.

Plaster Landscape, 1959, plaster, 48 x 24 x 3 inches

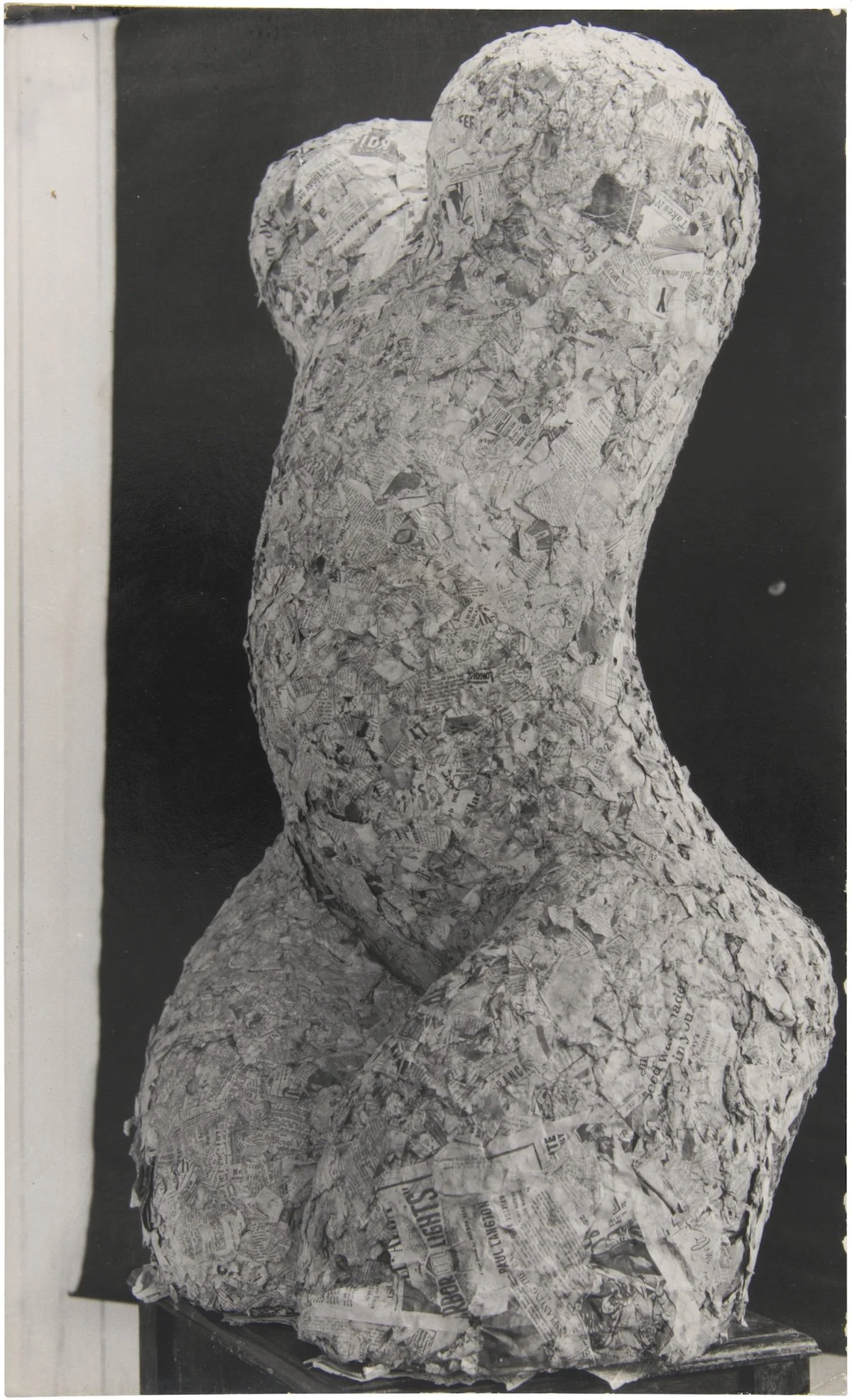

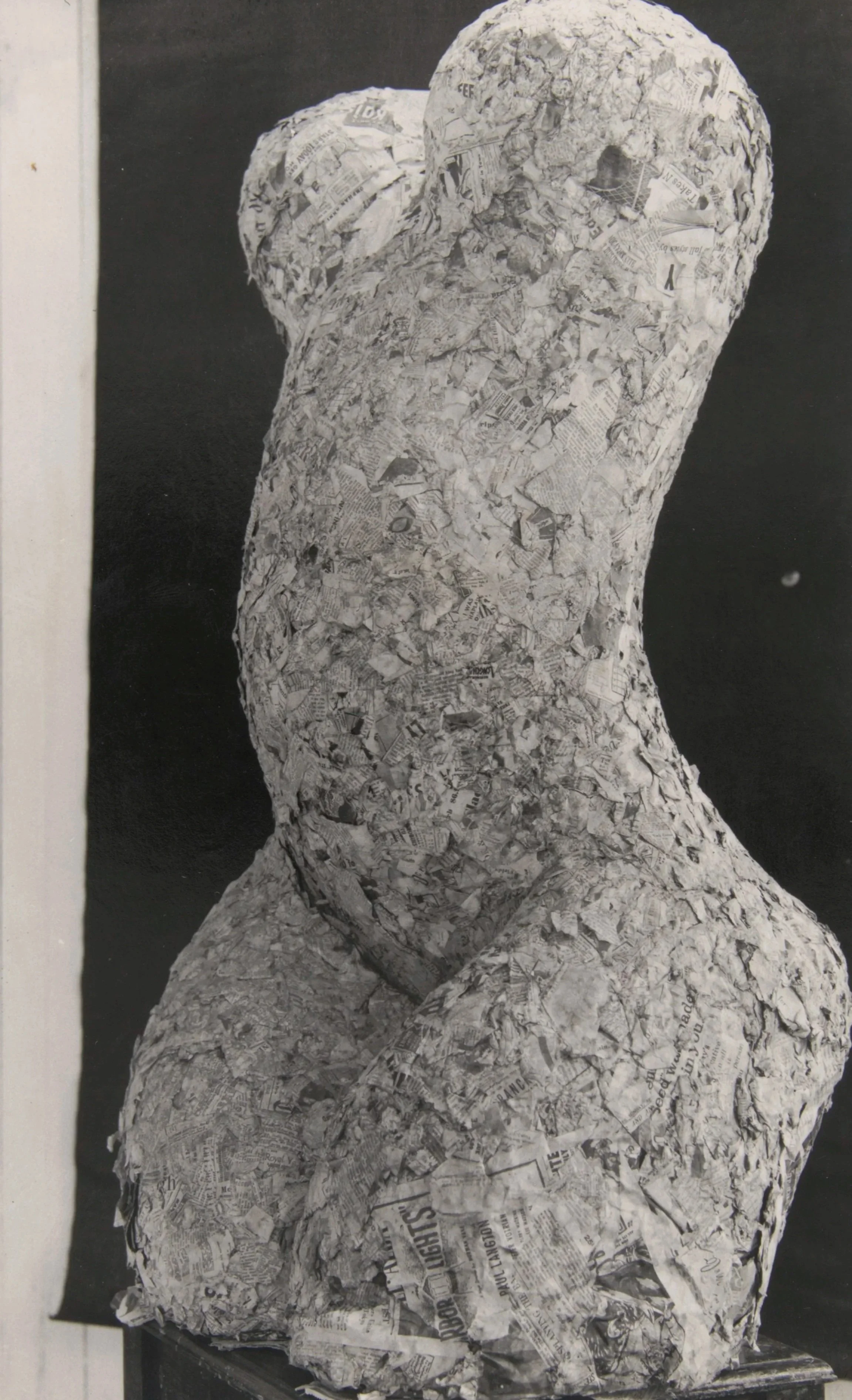

Torso I, 1958, papier-mâché,

48 x 25 x 23 inches

Chandelier of Love, 1960, plaster, 24 x 68 x 20 inches

By the end of the 1950s, Harris had largely moved on from papier-mâché, turning to other media he probably considered more sophisticated as his confidence as a sculptor grew. While he advanced his processes in fabric, string, and bronze at this time, he also worked with both plaster and concrete, with which he had previously dabbled. But between 1958 and 1960, Harris leaned into his sculpture in these media, which offered a plasticity akin to that of papier-mâché but were more historically aligned with the fine arts. Torso II (1958), one of his first fully developed concrete works, was made from a papier-mâché cast titled Torso I, though he later used plaster for these purposes. Overall, Harris tended to work representationally, but in these two media he frequently veered into the abstract. In plaster, he proved especially adept at drawing out softness from the dense material, making works like Plaster Landscape (1959) and Chandelier of Love (1960) that were billowy and voluptuous, with creamy surfaces that tempt one to caress them. Of Chandelier of Love, a critic writing on Harris’s 1960 show at Poindexter colorfully noted that it has a force “as irresistible as mushrooms breaking through cement floors,” and praised the body of work throughout the show for its magical and theatrical qualities.

Ever the innovator, Harris continued his experiments in three dimensions even late in life, evidenced, for instance, by his engagement with a series of wooden sculptures in the early 1990s, when he was in his mid-60s and by then well established in his career. The Nature Morte series (1991) saw the artist returning to the still life genre (which he had earlier explored in bronze and continued to address occasionally during his career in all forms of media), as well as the Nocturne series, another art historical motif, which relates to night scenery. In both these series, Harris’s finely honed wood elements are assembled together in refined, tabletop-sized works that teem with a life force only the deft hands of a master sculptor, confident in his facility with any material, could impart.

Nocturne I, 1991, wood, 11 x 67 x 30 inches