An Infinity of Forms

by Sarah Hotchkiss

It strikes me as particularly poetic that Paul Harris served his time in the Navy aboard the USS Ault, a destroyer painted in dazzle camouflage.

When it entered the Pacific Theater of World War II in 1944, the football field-length ship was adorned with an all-over mural of hard-edged geometric planes—a stylized cascade of “steps” in shades of black and gray. Instead of concealing a ship, dazzle camouflage was meant to confuse an enemy observer as to what exactly they were looking at. Where was the prow? What was the heading? How fast was the vessel really going?

The success of dazzle is debatable in all ways but one: it markedly improved morale. Within the senseless violence of war, strategically applied paint provided sailors with a sense of some protection.

Ship, Pacific Fleet III, 1945, pencil on paper, 11 ¾ x 8 ¾ inches

Aboard this floating artwork, shielded with an armor of paint, Harris drew. He drew his shipmates, tucked-away corners of the destroyer, his own hands. Sleeping sailors piled into their bunks were particularly good models. These drawings—quick, assured, shaded with graphite cross-hatching—set the stage for an aspect of Harris’s art practice that would persist for nearly the rest of his life, even as he became much better known as a sculptor working in fabric and bronze.

Back to that dazzle. Though Harris would draw many things over the course of his life—scenes from his travels, bouquets of flowers, nudes, self-portraits, abstract compositions—there is something solid, almost three-dimensional, about all of his works on paper. And I like to think that the illusory nature of the USS Ault’s geometric camouflage prepared him, in some small way, for the challenge of rendering volumetric forms and dense fields of color on pieces of acetate and paper. Later, Harris’s sophisticated sculptural work served as further evidence of his ability to move fluidly between two and three dimensions.

Harris rendered solidity through the thick graphite outlines of a model’s torso. He got at it by laying down colorful swaths of crayon, nearly opaque. In his drawings, bananas ripen, bodies sag, and shapes fit together with jigsaw-like precision. He saw, in drawing, not a flat surface, but “an infinity of forms yet to be born.”¹

Seaman, USS Ault, 1944, pencil on paper, 15 x 11 inches

Robert Jackson I, 1945, pencil on paper, 12 x 9 inches

Documentation & Fabrication

The fluid urgency of Harris’s wartime drawings comes from stolen moments and ad hoc materials. In some of these pieces, Harris drew on appropriated letterhead, scenes and figures crowded onto one sheet to save paper. He came into the war straight out of high school, but with a few classes at the Los Angeles art school Chouinard under his belt, and it’s clear he was already skilled at drawing from life.

Harris intended to continue his service after the war ended, but rheumatic fever put him into naval hospitals for six months. Future rearranged: By June 1946, he had enrolled at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque to pursue his BFA.

In 1948, during his junior year, he studied “abroad” in New York City at the New School for Social Research. It’s there that he met the German painter Johannes Molzahn, a member of the Bauhaus who fled the Nazis for the United States in 1933.

He wanted me to think about drawing in a way which was new to me,” Harris later wrote of Molzahn. “He urged me to see the white sheet of paper as a place of unlimited possibilities. ‘Look at it!’ he said, ‘Flat, clean and white — a world in which you are in charge. With one black line you can slice that white in two. But where you place that black line is absolutely crucial.’”²

“

Bananas, The Dancers, 2002, crayon on paper, 14 ½ x 16 inches

That exacting sentiment remained with Harris for over half a century. He had high standards for himself, so much so that he regularly edited his drawings down. That any remain feels like a small miracle. In an email to the poet Thom Gunn, Harris wrote, “I know I am not a great draughtsman” and “in drawing Paul is not first rate.” Some drawings were apparently “banished forever.”³

If a white sheet of paper is, as Molzahn said, a place of unlimited possibilities, Harris used his white sheets of paper as a place for both documentation and fabrication. He depicted what was at hand: people, places, fruit from his garden. (“I’m always looking around the house,” he said in a 2000 radio interview.) But he also took what could be familiar and tweaked it, going angular, stylized, or altogether nonrepresentational.

Harris met another influential figure during that school year, in the summer of 1949, when he took classes with the painter Hans Hofmann in Provincetown, Massachusetts. The ethos of Hoffman’s “push/pull” approach to arranging blocks of bright colors can be seen clearly in Harris’s later crayon drawings, in which recognizable forms battle with their backgrounds for dominance, creating sizzling, dynamic compositions

While Molzahn and Hofmann’s artistic influence on Harris’s life is undeniable, the most important person he met during his time on the East Coast was arguably Marguerite “Meme” Kirk, who he proposed to before returning to Albuquerque. They remained married until his death in 2018.

After graduation, Harris took a job teaching in Jamaica, where his growing family lived from 1952 to 1954, avoiding the McCarthyism sweeping American campuses. Harris’s drawings from this period have a USS Ault-esque rapidity, with more editorial flair. One gets the sense he was making his work in similar fits and starts, snatching time between teaching and raising two boys. Social and class commentary enters the work; Harris is no passive observer.

Many practical moves followed: a return to the States to escape a polio outbreak; Harris’s 1955 enrollment at Columbia to get an EdD (and better set him up for teaching gigs); a house in Glen Ridge, New Jersey, where Harris turned the garage into an art studio.

His work was gaining recognition in New York, but he also had a lot on his plate. A 1956 self-portrait in pastel shows a rather grim-looking Harris in a beatnik sweater, a piece his son Christopher later described as depicting someone “coming to the realization that his life as an artist was not carefree.”⁴ Despite Harris’s dour expression, the drawing is elegantly composed—he has clearly exerted his control over “the world” of this sheet of paper. Tightly cropped at Harris’s hair and propped-up knee, we see a young man with one arm extending off the page, the other ending in splayed fingers. His white sweater is made up of vertical strokes of pastel, emulating the downward pull of gravity. On that off-kilter face, the left side of the mouth drops dramatically—quizzically, skeptically.

The future was coming fast, and soon, life would take on a markedly sunnier sheen.

Self Portrait, 1956, pastel on paper, dimensions unknown

The Dreamy Path

Before a decade passed, Harris and his family escaped East Coast winters (thanks to the encouragement of Richard Diebenkorn), and bought a plot of land for $5,000 in Bolinas, California. Eventually, Harris would have two studios on the property: one for sculpture, the other for drawing.

For as much as Harris experimented across media—making textile sculptures out of upholstery, founding a press and publishing artist’s books, casting in bronze—drawing was a constant. He showed pastels and crayon drawings in a 1968 show at Folsom’s legendary Candy Store gallery, a hub of the Funk Art/Nut Art scene. In a Sacramento Bee review that compared him to Cézanne, Charles Johnson wrote, “In an era of hard-edge painting, surrealism, and a general mocking of all art of the past, Paul Harris pursues the dreamy path.”⁵

Bolinas Bouquet, 1968, crayon on paper, 15 ⅜ x 12 ½ inches

Thinking back to that gravity-bound figure in the 1956 self-portrait, Harris’s floral drawings from his Bolinas era are full of light and color. In the 1968 crayon on paper drawing Bolinas Bouquet, the contents of a green vase blend into the equally colorful foliage behind. There’s no telling where the bouquet ends and where the yard from which it came begins. The Harrises’ garden was a noted Eden: in the Bolinas soil and a greenhouse, Meme cultivated a year-round selection of flowers, vegetables, herbs and tomatoes. Some life simply is already art.

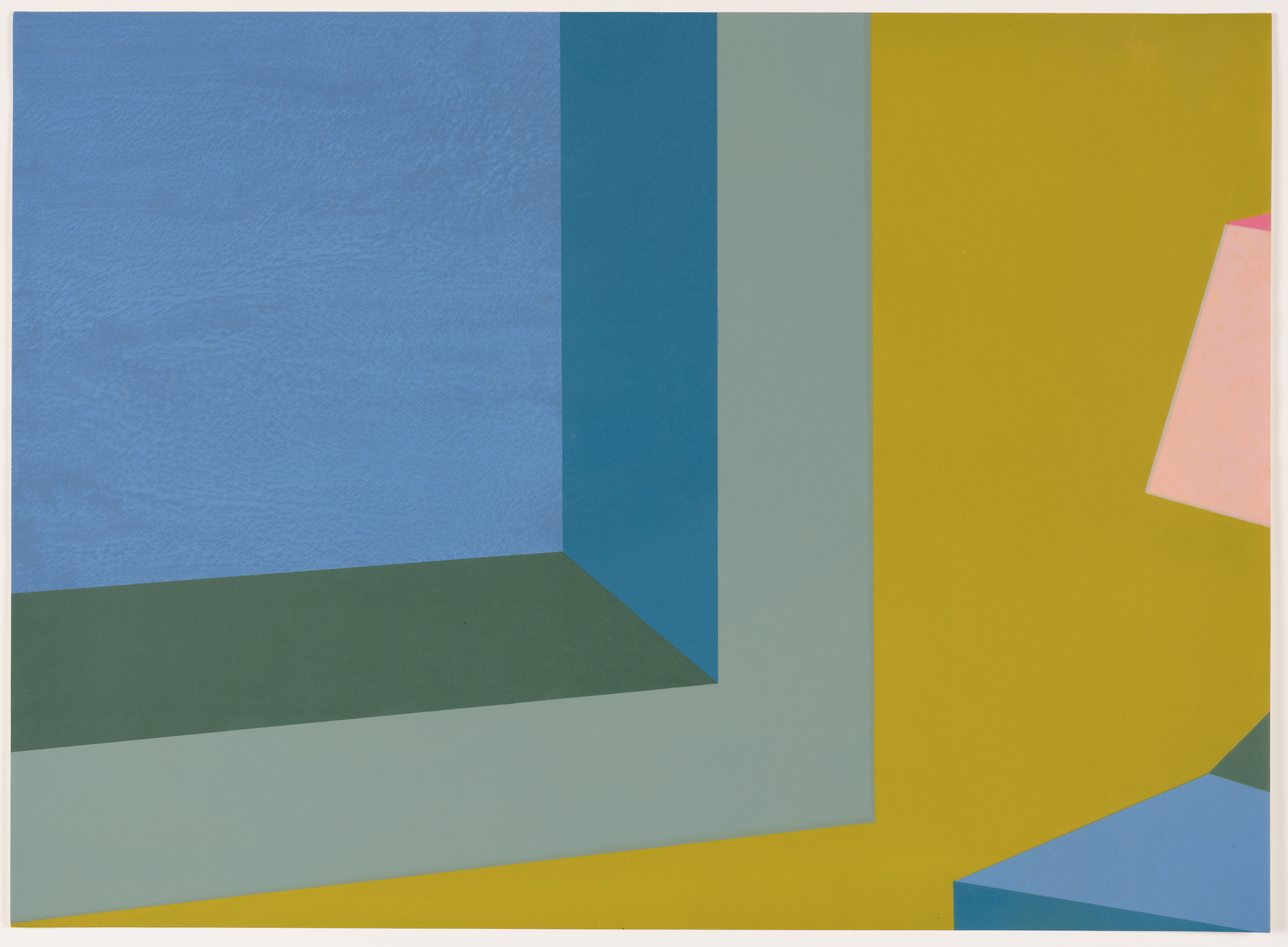

The next year, during a fellowship at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop, Harris created prints that further confused foreground and background with bright planes of color, interrupted patterns and inventive compositions. He was in Los Angeles for the fellowship for three months, but he spent all his waking hours either in the studio or a rented apartment nearby. He had little-to-no life outside of work and sleep. The resulting series, The Shut-In Suite, is crisp and claustrophobic. Many of the prints show interior spaces drenched in color, but oddly framed—off-kilter yet again. The fellowship press release describes “still lifes as seen through a zoom lens.” Another piece comes “from [a] worm’s eye view.”⁶

Until Harris retired from teaching at California College of the Arts in 1992, Tamarind was a rare period of single-minded devotion to his own practice, without responsibilities to family, students, school bureaucracy, or everyday life. His Tamarind time was productive (he completed 21 prints in those three months, all measuring 30 by 22 inches), but some of the vitality that Harris captures in his drawings goes missing in these prints. It would seem that the messiness of being in the mix of things—Harris’s practice of looking and finding “things around the house”—helped him create images that absolutely crackle with life. “I became very accustomed to crayons, and I’ve never been able to let them go,” Harris said in 2000. “Crayons are still my best friends in making drawings and I don’t think it will ever end.”⁷

Harris wasn’t able to keep drawing until the very end of his life; Parkinson’s prevented him from maintaining his exceedingly high standards past 2011. But what a pleasure it is to bear witness to the archive of works on paper he did produce (and held onto) during his long career. This unlikely “friendship,” laid down on paper again and again, produced reliably beautiful results. In his crayon on paper works, especially, we get to see the merger of the material with an artist’s confident hand. Just like visible brushstrokes, Harris’s path across the paper is evident, part of these works’ continued liveliness. Like in the 1983 piece Orange Hibiscus & Copa D’Oro, where yellow crayon arcs across a dark green field. Or in 1989’s Blue and White Bowl on Rag Rug, which showcases the full spectrum of textures Harris could create (sharp, blurry, rough, frenetic) with just one medium.

The Other Room, 1969, lithograph, 29 ¼ x 21 ½ inches

Blue & White Bowl on Rag Rug, 1989, crayon on paper, 11 x 14 inches

Montana, 2005, crayon on paper, 25 ½ x 32 inches

Harris’s final body of work began in the mid-2000s, with a turn to full abstraction. These pieces have representational or inscriptive titles (or both): Sundown for Leni, Montana, For the Shipmates 1944–1945. But there are no still lifes to puzzle out from their surroundings here. These are pure blocks of Hans Hofmann color, sometimes joyfully curvaceous. In the process of using his beloved crayon colors together within soft and hard-edged shapes, fitting them together with delightful precision, Harris came full circle. This dazzle, Paul Harris’s dazzle, isn’t contained to just one ship’s surface, or one hoped-for strategic military outcome. The Paul Harris dazzle is an infinity of imagined forms. “I began to see that drawing was a way to make things you didn’t have,” he wrote in 2007. “So draw.”⁸

Sarah Hotchkiss is an artist and writer in San Francisco, where she is a senior editor of arts and culture for KQED, the Bay Area’s NPR and PBS affiliate. She has written essays and reviews for Art in America, The Creative Independent, SFMOMA’s Open Space and Squarecylinder, among other publications. Her writing has been recognized by awards from the Dorothea & Leo Rabkin Foundation and the Society of Professional Journalists, Northern California.

-

¹Paul Harris, “Thoughts on Form,” undated.

²Paul Harris, “On Drawing,” Black & White: Drawings and Prints, 2007.

³Paul Harris email to Thom Gunn, undated.

⁴Michele Corriel, “Portraits of Himself: His Mirror’s Changing Reflections,” 2025.

⁵Charles Johnson, “Art Views: Descendant of Cezanne,” Sacramento Bee, April 28, 1968.

⁶Tamarind Lithography Workshop press release, “Paul Harris, Tamarind Fellowship Artist: November 1969–January 1970,” undated.

⁷Michele Corriel citing a KWMR radio interview, “Portraits of Himself: His Mirror’s Changing Reflections,” 2025.

⁸Paul Harris, “On Drawing,” Black & White: Drawings and Prints, 2007.